Last May, preservationists across Florida breathed a sigh of relief when a bill seeking to gut protections for historic coastal buildings died in the Florida House after passing the Senate. But similar proposals are back for this year’s legislative session in Tallahassee, sending local leaders scrambling once again.

On Monday, the Senate version of the bill passed its first committee hearing — a 6-2 vote of the Community Affairs committee — despite a parade of speakers saying they feared the language would let developers strip away the unique character of tourist destinations like Miami Beach, St. Augustine and Key West. At the legislation’s core is a notion that old buildings near Florida’s coast ought to be demolished if a local building official deems them unsafe or if they don’t meet federal standards that call for flood-resistant materials and elevated structures in vulnerable areas. Preservationists say few historic buildings conform to those rules.

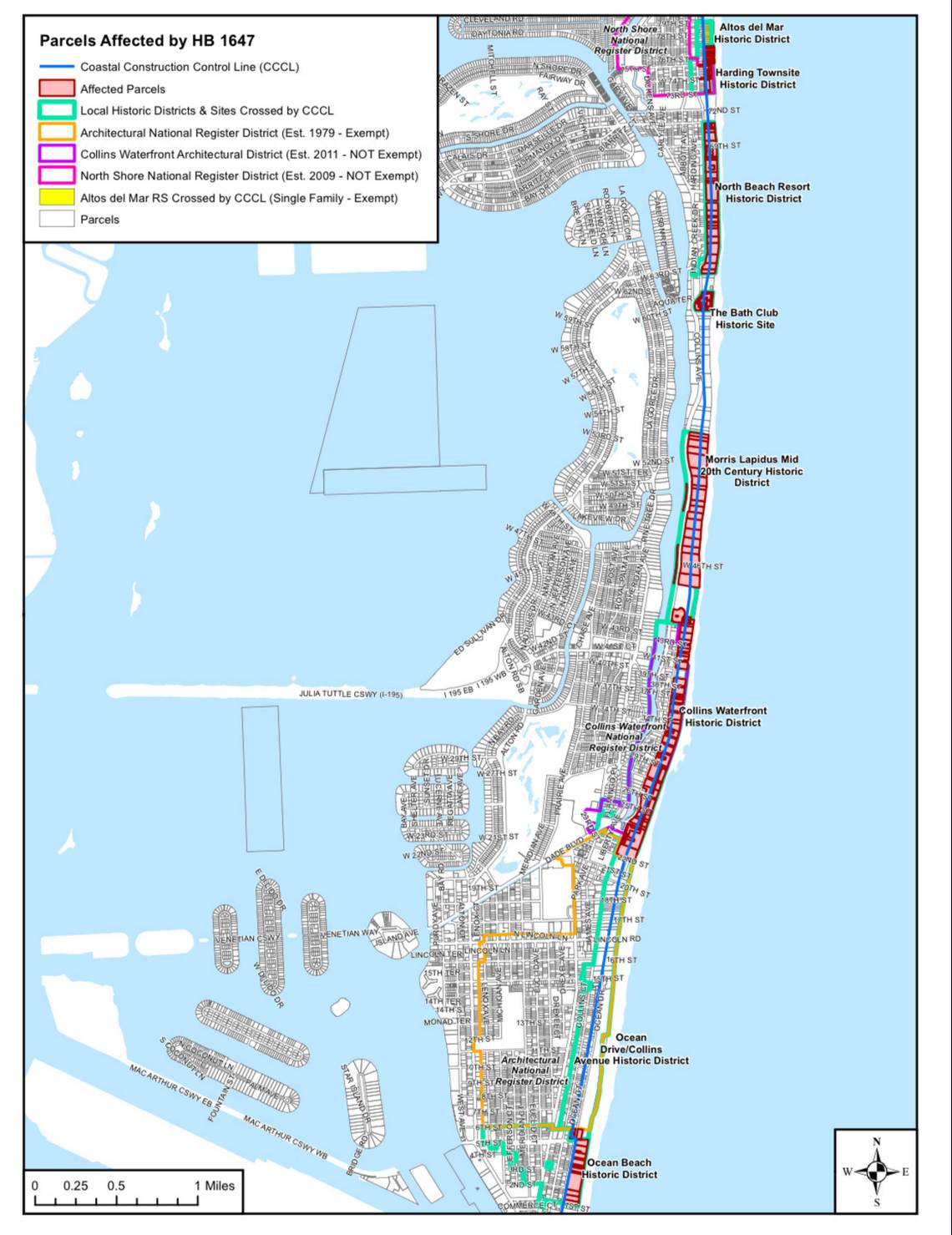

Both the Senate bill and its companion bill in the House would exempt single-family homes, as well as structures that are individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places. In Miami Beach, that includes the Fontainebleau, Cadillac and Ocean Spray hotels. But historic hotels along Collins Avenue in the Mid-Beach and North Beach neighborhoods would not receive similar protections under either proposal. Among them are Art Deco buildings like the Faena, Sherry Frontenac, Casablanca and Carillon.

The Senate bill sponsor, Bryan Avila, a Republican from west Miami-Dade, acknowledged during Monday’s hearing that the idea is controversial. His proposal would kneecap Miami Beach’s Historic Preservation Board, which is empowered to block demolition of historic buildings and, if a building is knocked down, dictate what can go in its place.

Avila reiterated arguments he made for similar legislation he filed last year. He painted Miami Beach as a community that has gone too far in its historic protections, upsetting what he described as a “very delicate dance” between preserving history and maintaining property rights. About 2,600 buildings in Miami Beach are part of locally designated historic districts.

HOUSE BILL WOULD SOFTEN THE BLOW

Rep. Spencer Roach, R-North Fort Myers, has filed a companion to Avila’s bill in the Florida House with language that would soften the legislation’s impacts. Last year, Roach abandoned a similar bill amid fierce opposition from local governments but vowed to bring it back in 2024. While Avila’s bill would affect buildings within a half-mile of the coast, Roach’s proposal is limited to properties at least partially east of the state’s coastal construction control line, a boundary that hugs the coast and is meant to restrict construction near beaches. Roach’s bill, which has not yet faced a hearing, would also exempt buildings in nationally designated historic districts established before 2000 — meaning the Miami Beach Architectural District, an area that stretches from Ocean Drive at Sixth Street to Collins Avenue at 22nd Street, would be protected.

‘BAD, BUT LESS BAD’

Facing questioning Monday from Sen. Jason Pizzo, D-Hollywood, Avila pledged to revise his bill to make it more like the House version.

“I am committed to going in that direction and working with the House sponsor to adopt that language,” he said. Avila did not respond to an inquiry from the Miami Herald on whether he would adopt the entire House bill or parts of it. The House bill is “bad, but less bad than [the Senate] one,” said Daniel Ciraldo, executive director of the Miami Design Preservation League, which advocates for historic preservation in Miami Beach. “They’re trying to undo decades of good urban planning and community consensus building,” Ciraldo said. “We’re basically trying to explain why Miami Beach should still exist.”

Miami Beach City Commissioner Alex Fernandez said at Monday’s hearing that the city has worked cooperatively with owners of historic buildings to revitalize Art Deco gems, pointing to a $500 million renovation of The Raleigh and an $85 million makeover for The Shelborne.

The proposed legislation, Fernandez said, would only encourage owners to let their properties fall into disarray in order to incur unsafe structure violations and make it easier to knock buildings down. In Key West, Mayor Teri Johnston said she hopes the city will ultimately be removed from the legislation. Last year, language added to Avila’s proposal exempted “areas of critical state concern,” which includes Key West and much of the Florida Keys.

‘WHAT HAPPENED TO PROPERTY RIGHTS?’

Lawmakers supporting the bills say property owners should have more freedom to develop than Miami Beach and other cities with strict historic protections allow.

“What happened to property rights?” Sen. Dennis Baxley, R-Lady Lake, said at Monday’s hearing. “Everybody else has a claim to somebody’s property but the person that owns it, apparently. I don’t share that viewpoint.”

The bills’ backers also say the changes are crucial to ensuring building safety and resiliency against flooding near Florida’s coast. Last year, Avila argued it was necessary to replace older buildings with new structures that meet FEMA rules for flood- and storm-surge resistance to obtain insurance under the National Flood Insurance Program.

Opponents say they’re skeptical and that they believe powerful — and secretive — interests may be behind the effort. Last year, a group called A Resilient Future Florida hired a lobbying firm to push for the bills, according to public records. One of the firm’s lobbyists, Gov. Ron DeSantis’ former chief of staff Adrian Lukis, sent a draft of the legislation to staffers for Avila and Roach, according to records obtained by reporter Jason Garcia.

But it’s unclear who is funding the group, which donated $40,000 late last year to several political committees supporting Republican lawmakers. It was incorporated last March by Tallahassee elections attorney Natalie Kato and lists two Jacksonville residents, Joey McKinnon and Casey Hendershot, as its officers. Reached by phone, McKinnon and Hendershot declined to talk about their roles in the group or what it does, referring questions to Kato. Kato did not respond to a request for comment. This year, records show the group has again retained Lukis to lobby on the legislation. Lukis did not respond to a request for comment.

Source: Miami Herald